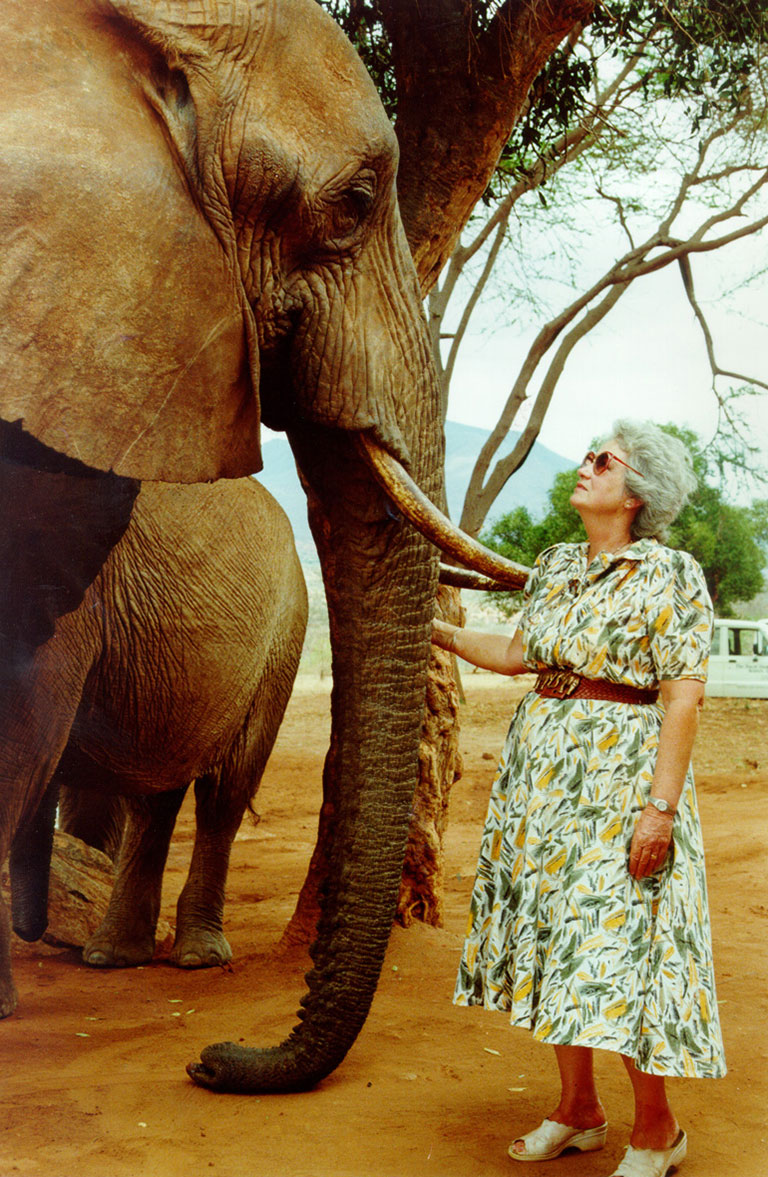

Dr. Dame Daphne Sheldrick of DSWT

Dr. Dame Daphne Sheldrick was a celebrated author, conservationist, and expert in animal care and rehabilitation. In 1977, in memory of her late husband, she founded the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, a conservation center in Nairobi, Kenya, whose acclaimed Orphans’ Project has achieved worldwide renown through its pioneering elephant and rhino rescue and rehabilitation program. The orphanage is a haven for young rhinos and elephants whose parents have been killed by poachers for their ivory and horn. For her work in this field, Sheldrick was decorated by the Queen with an Order of the British Empire (Damehood), honored by the Kenyan Government with a prestigious Moran of the Burning Spear, and awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Veterinary Medicine and Surgery by Glasgow University. In 2002 she received the BBC’s Lifetime Achievement Award. Daphne’s life’s work was the subject of a critically acclaimed 3D Imax film, Born to Be Wild, and her memoir, Love, Life and Elephants – An African Love Story is a national bestseller. Daphne Sheldrick was considered a leading international authority on the rearing and care of wild creatures, and was recognized as the first person to have perfected the milk formula and life-saving feeding protocol for orphaned milk-dependent elephants and rhinos.

Daphne Sheldrick passed away in April of 2018 after impacting the lives of countless humans and animals. In the Fall of 2014 we were honored to have her as our first interview. Rest in peace Daphne, and thank you for impacting the lives of countless animals and humans, and making the world a better place for us all.

What have been the greatest lessons the elephants have taught you? And what can humans learn from them?

Elephants can teach us humans about caring, about being gentle despite being powerful, about cooperation, and about forgiveness. Examples of all of these traits can be found in our monthly Keepers’ Diaries, which chronicle all the happenings of the elephants in our care on a daily basis, and in the Trust’s Annual Newsletters, which are posted on our website.

Rearing the orphaned elephants has taught us (and the world generally) a great deal about “the inside story” of elephants – how they feel and how they think and how essentially like us they are. To understand almost any elephant behavior, one need only interpret it in human terms to get close to the truth. It is humbling to know and accept that we are not above others of the natural world, and that the world did not evolve just to accommodate us humans, but that every species is vital to the wellbeing of the whole. We humans have stepped out of line with nature. We are destroying the planet, and, ultimately, ourselves, if we continue along this same path and do not nurture the natural world and the environment that is key to the wellbeing of all life.

In what ways are elephants most like us?

The simple answer is that they have all the best human qualities and few of the bad.

We humans tend not to attribute human-like intelligence to other animals in the natural world, and that merely shows our gross ignorance. This thinking is flawed, because all animals, including the antelopes, birds, fish, and even reptiles, are intelligent in their own way; they have simply evolved on a different branch of life. Elephants, however, are in my opinion just like us, and much better than us in many ways, as are whales and dolphins and, in fact, many other members of the Animal Kingdom. Few take pleasure in killing just for the sake of killing, unlike humans who do so happily under the guise of “sport hunting” — !

It is humbling to know and accept that we are not above others of the natural world…

In your autobiography, An African Love Story: Love, Life and Elephants, you wrote about so many incredible things that you had witnessed living among elephants. Can you describe some of them in more detail?

One of the greatest experiences that I have been privileged to enjoy is when our Ex Orphans (Ex Orphans are orphaned elephants who were raised by us and rehabilitated back into the wild) bring their wild babies back to share with their extended human family. Ex Orphan Mulika brought little Mwende back to meet me on the very day she was born, seeking me out at the Ithumba mudbath; Yatta brought her baby Yetu back to meet the Keepers at Ithumba, and Emily brought little Eve back to meet the Voi Unit Keepers. Even Ex Orphan Lissa, who has 4 wild-born babies, brings them back to the Stockades whenever she happens to be nearby.

I was also amazed the first time I realized that elephants can communicate sophisticated messages to one another. We see many examples of this at the Trust. Our Ithumba Ex Orphans frequently bring their wild friends into the refuge’s mud baths, and those wild elephants, who behave very differently out in the bush when they encounter humans, are able to recognize that here are individuals they can trust.

It is also a remarkable thing to witness wild-living Ex Orphan elephants chaperone Keeper Dependent Juniors (young elephants who still live with their human keepers) for a day or night outing into the bush, and then escort them back to their Keepers in the evenings. To see our orphans recover from terror and a state of near death when they are rescued, and begin to play and become happy again, gives us all a great lift. Just watching our orphans and knowing that because of the Trust, they have been granted a second chance at life, and, more importantly, a wild life, makes me, and us all, extremely happy.

Another exceptional behavior observed in our orphans is that they are able to recognize Keepers they have not seen for many years. When Eleanor was in her forties and living wild again, she recognized a Keeper she had not seen since she was about the age of five years. And when our elephant nursery workers, known as Nursery Keepers, transfer Ex Nursery babies to the Rehab Centres in Tsavo, and the older Ex Orphans are in the vicinity, they instantly recognize the Keepers they knew in early infancy. We have witnessed this time and again. On one such occasion the Nursery Keepers were so overwhelmed that they began to cry, because they had not at first been able to recognize the persistent attention of one particular Ex Orphan as the overjoyed greeting of a baby they had nurtured as a newborn!

What advice would you give to people who want to help elephants? What can we do to protect them and safeguard their future?

Only completely banning the domestic ivory trade in China and elsewhere will save the elephants. But everyone can do something to help protect and save the elephants, however humble. Protecting elephants as a species involves money, and every contribution helps, no matter how small. Our orphan elephants can be fostered for a minimum donation of $50 a year, and sponsors are rewarded with monthly updates about the orphans as well as with a watercolor painting and recent photographs of their foster elephant. But we do a great deal more than just raise the orphaned elephants; we run four mobile veterinary units, nine anti-poaching teams, four aerial surveillance aircraft and a helicopter in support of our field teams. We work tirelessly to conserve threatened habitats, and we have developed a substantial community outreach program. All of these efforts are necessary to the protection of the elephants and need the support of donors. Donations can be made to each of the various projects on our website.

Everyone can do something to help protect and save the elephants, however humble

Many children across the globe have raised money for the elephant cause by baking cakes, washing cars and helping with housework. People all over the world love and cherish the elephants, and cannot contemplate a world without them.

Will you leave us with one of your most memorable experiences with elephants?

The following is excerpted from the Prologue to Love, Life and Elephants – An African Love Story, by Dr. Dame Daphne Sheldrick

The day had begun well. My friend and I were in Tsavo National Park, among the tangled vegetation and wild herds, searching for Eleanor. I was eager to find my most treasured orphaned elephant. Over my many years of involvement with elephants, there was no doubt about it: Eleanor had taught me the most about her kind. We had been through many ups and downs together. She was my old friend.

…At last – in the right area – we spotted a wild herd. From a distance it was never easy to identify Eleanor among a milling crowd of her fellow adults, and I had never felt the need to do so, certain that she would always know me. Unlike the other wild elephants of Tsavo, who had no reason to either like or trust humans, Eleanor would always want to come when called, to greet me, simply for old times’ sake. I have come to know a lot about elephant memory and how very similar to ourselves elephants are in terms of emotion – after all, greeting an old friend makes you feel good, remembered, wanted.

There stood a large cow elephant drinking at a muddy pool, her family already moving off among the bushes. From this distance, it didn’t look much like Eleanor, for although as large, this elephant was stockier. I told my friend as much. ‘How disappointing,’ he said. ‘I was so hoping to meet her.’ ‘I’ll call her,’ I replied, ‘and if this is Eleanor, she will respond.’ She did. The elephant looked up at me, her ears slightly raised, curious. She left the pool and walked straight up to us. ‘Hello Eleanor’ I said. ‘You’ve put on weight.’ I looked into her eyes, which curiously were pale amber. I had a fleeting thought that Eleanor’s eyes were darker, but I dismissed this instantly. This must be Eleanor. Wild elephants in Tsavo simply did not behave this way, approaching humans so trustingly. The Tsavo herds were now innately suspicious of our kind, having been relentlessly persecuted in the poaching holocaust of the 70s, 80s, and early 90s. ‘Yes,’ I said to my friend. ‘This is Eleanor.’ Reaching up, I touched her cheeks and felt the cool ivory of her tusks, caressing her below the chin in greeting. Her eyes were gentle and friendly, fringed with long dark lashes; her manner was welcoming.

‘She’s beautiful,’ murmured my friend. ‘Stand next to her so that I can take a photo.’ I positioned myself beside one massive foreleg, reaching up my hand to stroke her behind the ear, something that I loved doing with Eleanor. The hind side of an elephant’s ear is as soft and smooth to the touch as silk and always deliciously cool.

I was totally unprepared for what happened next. The elephant took a pace backwards, swung her giant head and, using her trunk to lift my body, threw me like a piece of weightless flotsam high through the air with such force that I smashed down onto a giant clump of boulders some twenty paces away. I knew at once that the impact had shattered my right leg, for I could hear and feel the bones crunch as I struggled to sit up. I could see that I was already bleeding copiously from an open wound in my thigh. Astonishingly, there was no pain – not yet, anyway.

My friend screamed. The elephant – I knew for certain now that this was not Eleanor – rushed at me, towering above my broken body as I braced myself for the end. I closed my eyes and began to pray. I had a lot to be thankful for, but I did not want to leave this world quite yet. Inside I began to panic, jumbled thoughts crowding my mind. But suddenly there was a moment of pure stillness – as if the world had simply stopped turning – and as I opened my eyes I could feel the elephant gently insert her tusks between my body and the rocks. Rather than a desire to kill, I realized that the elephant was actually trying to help me by lifting me to my feet, encouraging me to stand. I thought: this is how they respond to their young. But lifting me now could be catastrophic for my broken body. ‘No!’ I shouted as I smacked the tip of the wet trunk that reached down to touch my face. She gazed down at me, her ears splayed open in the shape of Africa, her eyes kind and concerned. Then, lifting one huge foot, she began to feel me gently all over, barely touching me. Her great ears stood out at right angles to her huge head as she contemplated me lying helpless, merely inches from the tip of two long, sharp tusks. I knew then that she did not intend to kill me – elephants are careful where they tread and do not stomp on their victims. If they do intend to kill, they kneel down and use the top of the trunk and forehead.

And it was at this moment – with an astonishing clarity of thought, that I can still feel within me to this day – I realized that if I were to live, I needed to fulfil the debt owed to Nature and all the animals that had so enriched my life. For even as I could feel the broken bones within my crumpled body, feel the fire of pain now engulfing me, and even though it was one of my beloved creatures that had caused me this distress, I knew then and there that I had an absolute duty to pass on my intimate knowledge and understanding of Africa’s wild animals and my belonging to Kenya.

I thought: if I survive this, I will write. This will be my legacy. I will set down everything I have learned in my efforts to contribute to the conservation, preservation and protection of wildlife in this magical land. It was as if this elephant had heard my thoughts. There was a tense silence as she took one more look at me and moved slowly off. I would live on.

Visit the website for the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust

Follow them on: